The Roman amphitheater of Merida was inaugurated in 8 B.C. and was the site of the famous gladiator fights.

Over the centuries, the amphitheater underwent several modifications and was used for religious and political events, as well as cultural and sporting functions.

Today, the Roman amphitheater of Merida is one of the main monuments of the city and is used as a place of entertainment and education. A must-see if you come to the city of Merida.

360º virtual guide through the amphitheater of Augusta Emerita

In this video, Gaius Valerius explains the Roman amphitheater of Merida in a virtual tour of 2 minutes and a half.

Interesting facts about the construction of the amphitheater and its parts

- The choice of the place where the amphitheater of Merida was built is not accidental, since here there is a small hill that could be used in the construction of the stands.

- These buildings accommodated large numbers of people, which is why, in Roman cities, they are always located on the outskirts.

- Their location also coincides with the crossroads between two Roman roads. At first, they were outside the walls, but over time they were extended and these monuments were left inside.

- The technique for building the amphitheater consisted of creating sections of walls on the natural slope of the hill. These walls were closed in rectangles that were then filled with Roman concrete.

- The shape of the amphitheater is not an ellipse as has been erroneously believed. It cannot be so because it is impossible to make concentric ellipses so that they are parallel. The figure used is the oval.

What were the bleachers and the arena like?

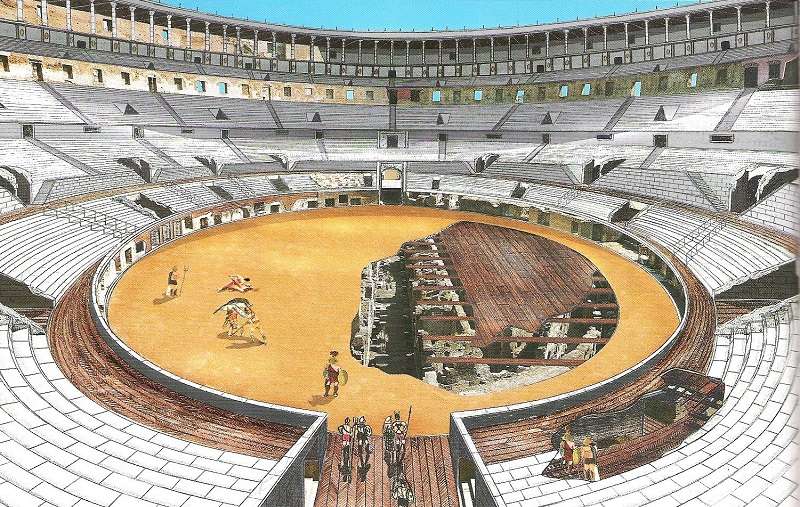

The amphitheater of Mérida had a capacity of about 15,000 spectators. Unlike the Theater, in the Amphitheater men and women could sit together to watch the show. Only the upper tiers were intended for servants, the poor and slaves.

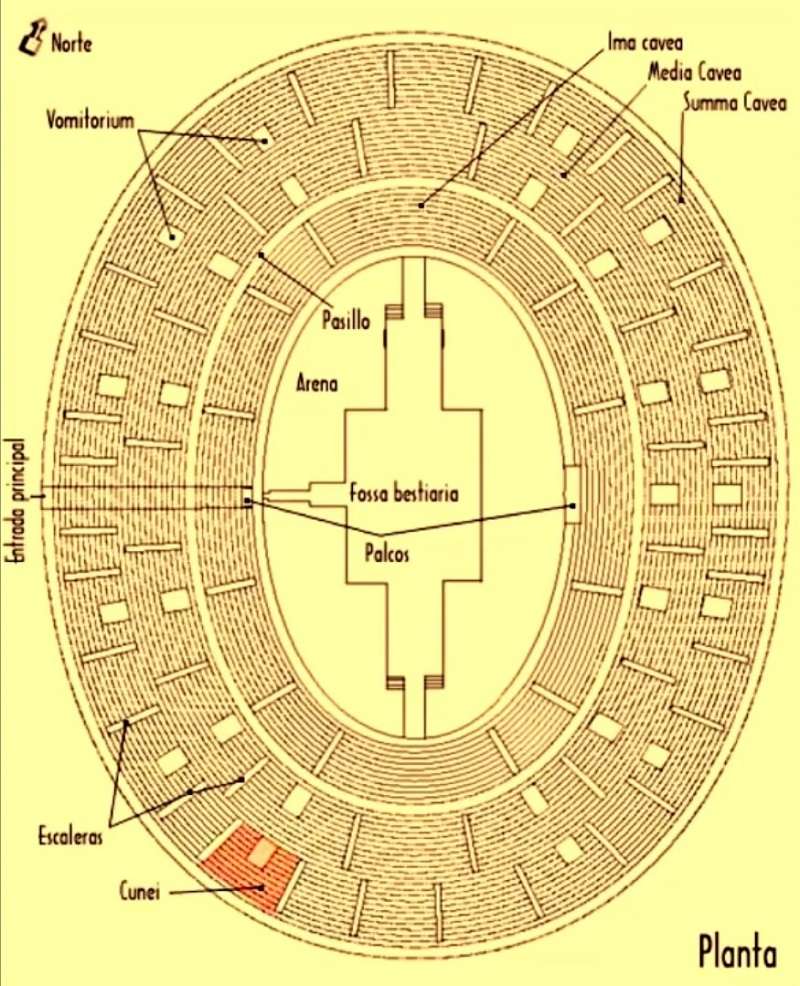

The stands were distributed in three zones called ima, media and summa cavea, that is, lower, middle and upper. They were separated by a brick wall, while the access stairs divided them into sectors.

Currently, only the remains of the middle and lower zone are left.

The amphitheater has 16 doors distributed around the entire floor called vomitoriums. The main one is the one through which the authorities and those who had paid for the show had access to the enclosure.

There were two grandstands, one in front of the other. To the west was the grandstand reserved for the authorities, and to the east for the person who financed the show. On the fronts of both grandstands there are two large inscriptions where the date of the inauguration is written.

The stands and the rest of the bleachers were separated from the arena by a balustrade. On top of the balustrade, nets were placed to prevent any of the beasts or any object from going against the audience.

The sand pit was covered with a wooden platform. Here were stored all kinds of materials needed for the performances, including the cages for the animals. Since this was the lowest point of the building, the water that drained during the rainy season had to be led through large pipes to the sewage system.

At the ends of the greater side of the amphitheater there are two large gates. On the left the Porta Pompae and on the right the Porta Triumphalis.

The games: the great spectacle of the amphitheater of Mérida

In the Roman amphitheater of Merida the most popular shows of the city were held. These were, above all, the famous games.

The games lasted a full day, were free and usually consisted of fights between gladiators, fights between animals and the combination of both: animal and gladiator.

The magistrates and the important people of the city paid for the organization of the games, which were always in honor of one of the Roman gods, and served as political propaganda.

Days before the event was announced in the city who was the organizer and how many pairs of gladiators would participate.

The night before, the gladiators were offered a plentiful dinner, and on the day of the games they were richly dressed and walked through the city in the direction of the amphitheater.

On the day there were games, the surroundings of the amphitheaters were filled with stalls selling food, people predicting the future, dancers and countless people who wanted to enter the enclosure.

We know that here in Merida the games lasted until the 5th century, coinciding with the arrival of Christianity.

Some curious facts about gladiatorial fights

Once the tour of the city was over, the gladiators entered through the Porta Pompae and the people cheered and shouted for them.

They were real heroes for the public.

The typical gladiator sword was the gladius, a short sword whose origin derives from the Iberian falcatas that the Romans knew in the wars against Hannibal.

In fact, the term gladiator comes from gladius (short sword).

When they arrived at the arena, they performed a drill with wooden or blunt weapons to prepare for battle.

It was time for combat, and it was the magister (old veteran gladiators) who chose the gladiators to fight.

To signal the start of combat, a horn was blown and then madness broke out.

When one of the gladiators managed to defeat his opponent, he would ask the audience to kill the defeated or not.

If the spectators understood that he deserved forgiveness, they would lower their thumbs, indicating that the winner should throw his weapon to the ground. Even then, only 10% died and usually from accidental wounds in the fight.

If the death of the defeated opponent was desired, what was done was to direct the thumb in a horizontal position and with a series of movements in the direction of the body pointing to the fateful point where the mortal blow should be directed.

The belief that cinema has shown us that thumbs up meant forgiveness and thumbs down meant death is erroneous.

Gladiators who died in the arena were dragged out by the slaves who served the amphitheater.

Los gladiadores que ganaban recibían premios como palmas, coronas adornadas de cintas y monedas. En los tiempos del imperio, una gran cantidad de dinero. Tenían el honor de salir por la puerta triunfal.

They could be prisoners of war, slaves or free men in search of a better future, since in addition to the prizes they could obtain the longed-for freedom.

To participate in the games, all gladiators had to take an oath that they would be whipped with rods, burned with fire and killed with iron.

There were gladiatorial schools where they specialized in a type of combat and weapon. After three years they could graduate and become instructors or continue fighting.

Frequently Asked Questions

The normal ticket price is 12€ (includes Theater and Amphitheater).

The reduced rate is 6€ and applies to young people between 13 and 17 years of age, youth card holders, students up to 25 years of age, seniors over 65 or retired, disabled persons and members of large families.

You can enter for free only if you are a Mérida resident, researcher, MECENAS member or under 12 years old.

The Theater’s winter schedule (from October 1 to March 31) is as follows:

Opening of the Monumental Enclosure: 9:00 a.m.

Closing of Box Office and Access: 6:00 p.m.

Closing of the Monumental Enclosure: 18:30 hours

Remember that you can also access the theater to see a performance even at night.

The Theater will be closed only on December 25, January 1 and January 6.

Of course! Check out the best guided tours in Merida.

The address of the Roman Amphitheater of Merida is Plaza Margarita Xirgu, s/n, 06800 Merida, Badajoz. You can see the location on the map here.

More of Merida’s historical heritage

Roman Theater of Merida

Roman Circus of Merida

Moorish Alcazaba of Merida

Roman Bridge of Merida over the Guadiana river

Co-cathedral of Santa María la Mayor of Mérida

Los Milagros de Merida Aqueduct

Roman Temple of Diana in Mérida

Casa del Mitreo House in Mérida

Portico of Merida’s Municipal Forum

Morería de Mérida Archaeological Site

Plaza de España in Mérida

Basilica of Santa Eulalia in Mérida

National Museum of Roman Art of Mérida

San Lázaro Aqueduct in Mérida

Merida Amphitheater House

Trajan’s Arch of Mérida

Mérida’s Xenodoquium

Roman Bridge over the Albarregas

Círculo Emeritense in Mérida

Mérida City Hall

Bullring of Mérida